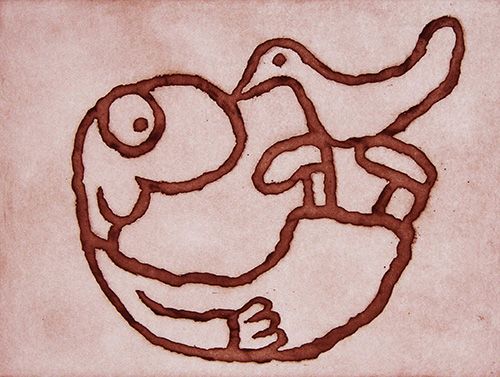

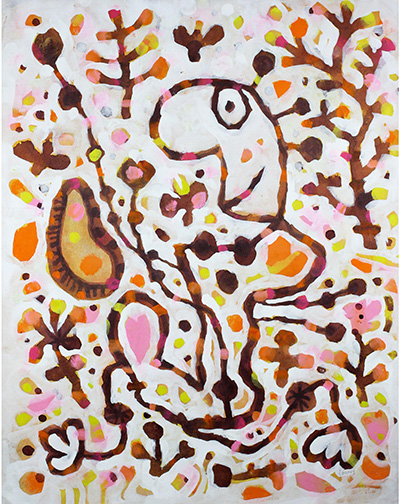

A peculiar central character has inhabited my drawings and paintings for as long as I care to remember; an abiding mysterious protagonist for whom I have maintained a deep respect and warm regard over many years. The term 'central character' could be misleading because this individual is by nature peripheral, unimposing and lowly.

I am not really sure if this being is a male or a female – or a child or an adult, and it doesn’t bother me that I don’t know or don’t care. Mostly the character looks pathetically ill defined – but enchantingly so in my view. Furthermore, I’m not even sure if this ‘person’ is fully human – it looks quite sub-human or creaturely in a primal humorous sort of way.

Yet it persists, and there it is again, I can’t stop it – wandering semi-consciously from my hand and off my pen or brush onto the paper - with its wide wondering eyes and foolish grin – or a dopey downcast gaze. A corny cartoon character. A nature loving fool. A sensitive soul. A free spirit. A joyous innocent. A shabby wanderer. A dawdling playful simpleton…

Years pass and very little changes. Its nose remains as absurdly large and cumbersome as ever. Its vulnerable demeanor remains more or less constant. The same ducks and fish and flowers are usually nearby; the same bird, the same teapot, the same crescent moon. Again and again, on the canvas or paper in front of me, these symbols recur, always a bit different but always much the same. In a world plagued by freakish novelties, constancy and simplicity become consoling ideas. On a voyage where so many and so much are rocking the boat, it becomes a serious vocation just to keep things steady.

Only in recent times have I come to realize that what I have been so constantly depicting is the world of the holy fool: the people, the creatures, the circumstances and the peculiar ecosystem of the spirit. If you yearn for something you may end up creating it.

This archetypal being called the holy fool, with its expressive outsider ways, its simple gestures, its joy and pathos, its unabashed authenticity and felt life, its naturalism and rejection of worldly sophistication lives somewhere beyond the horizon of modern life – or else in the primal playful reaches of imagination; a humble being who stands in sharp contrast to the common aspirations of contemporary urban humanity. Perhaps its existence in the mind is a natural antidote to fashion, political consciousness and the cult of cleverness, which so stifle and afflict creativity in Western culture.

In tradition, it is the fool who, to their apparent worldly disadvantage, says out loud quite cheerfully what others only dare to whisper. Yet it is the fool who brings relief and healing by expressing what has been repressed, or by articulating some unspoken universal grief. In some respects as much divine creature as human being and as much an innocent child as a visionary prophet, the holy fool recurs in history as a truth speaker such as St Francis of Assisi or Lao Tzu.

Yet there is surely a measure of the holy fool in all of us. What adult has not been a delightful or shocking little holy fool in childhood: the primal young creature who reached out innocently for what was forbidden, or sincerely said out loud a simple embarrassing truth? ‘The emperor has no clothes’ cries the wee holy fool. And who did not draw and paint in beautiful peculiar ways, or cry and sing freely for a short early chapter of wide-eyed creative life before the ways of the world began to impinge and inhibit? Who has not known a time of free flowing reverie and wonder in the rich solitude and sanctuary of early consciousness? Whose outlook and imagination has not been indelibly adorned by the daydreams and visions of childhood? The healthy child is the holy fool in exquisite miniature.

The divine fool exists in our early layers of personal history – where it may lie repressed, ignored or forgotten. There it waits! Unassuming, unkempt and unambitious, its regressive ways have little apparent value in a progressive world where excellence awards are ubiquitous, where prestigious success is an upward common compulsion and creativity is pursued with such earnest energetic method and intellectual intensity as to constrict the very possibility of its flourishing.

The dire pursuit of creativity in affluent societies is to a considerable extent driven by egotistical art ambition, but underlying this drive may be an intuitive attempt to recover the capacity for wonder, spontaneity, playfulness, openness, mindfulness and access to raw beauty; the qualities that were so natural and easy in childhood; a search for connection to one’s lost little fool - who is indeed the archetypal personification of creativity's wellspring.

Of course no adult can become an innocent child again but they may be able to find an unbroken path through imagination, intuition and sensual memory - back to impressions of infancy or early states of mind, and through a fruitful experience of this connection develop an adult capacity to reliably access a condition of humility, equanimity, openness and wonderment that we might call mature innocence. Thus the holy fool may appear and the constricting curses of compliance, cleverness, sophistication and insecurity may begin to dissolve.

Memory of childhood can help in the recovery of creative self but one of the most radical ways back to a state of discovery and playful creation is the messy path of unexpected regression. There are painters who often experience this and have learned that painting teaches much about failure and redemption – the dynamic that lies at the heart of creativity. The artist needs to know how to lose the plot – how to not care and how to not know – and how to actually enjoy that freedom and understand what a blessed revitalizing state all of that mess can be.

It could go something like this: the painter might begin a piece of work with high hopes and set forth with an interesting or brilliant idea in mind, but all too soon the painting begins to fail, the idea collapses and ambition starts to sour. The transcription from the intellect to the canvas is looking lifeless and artless, and the painter is starting to feel despondent. It's not working! How often it is that the mind and the hand have lost touch with each other. The painter redoubles all efforts but this only makes things worse and regression is happening as dismay and disillusionment set in. Soon enough the painting is in a miserable mess and everything is in disarray. It looks awful and the painter is emotionally heavy with self-doubt and disappointment. The worst has happened, the situation is lost and the painter's ego is peeling away. Little is it understood but at last the painter is breaking free, albeit a free fall – into a disturbing state of not knowing. The regression deepens, reason has fled while tantalizing and delinquent infantile impulses are felt: the petulant desire to destroy the painting and get rid of the evidence; the painful reminder of inability and failure.

At this point one of the noble truths of creativity may begin to emerge: 'disillusionment precedes inspiration and growth'. So instead of abandoning the failure as many would, the artist recognizes an opportunity to be free and play about casually or recklessly in the ruins; to experiment and throw all cautious technique, all self criticism and high standards to the wind because now there is nothing to lose and nobody is watching. Before long the painter has forgotten the failure and becomes absorbed in the anarchy of spontaneous gestures and spirited whimsical play. The holy fool and originality are at hand. The artist is painting unselfconsciously and with happy abandon – and somewhat like a child. To hell with solemnity and proper art; the joy of discovery is all that matters now; the unprecedented textures, the way the colours have by chance smeared into each other: beautiful startling subtleties and unimagined miracles small and large to delight or shock the eye. And so it proceeds until the painter is staring in fascination at this revelation that the hands and impulses have created in a state of regression; a state that could not have been planned or organized - but simply happened when ego and ambition had sufficiently crumbled.

It is a way of painting. It is a way of living. It is a way of transcending the banal inhibited self and finding the divine. It is a struggling downward journey - this stumbling, daring and devout pilgrimage back to mature innocence and raw beauty; to the sublime joy and the natural intelligence and wisdom of the holy fool.

‘True art does not look like art’ said Lao Tzu, and if we can entertain this promising idea we might also begin to imagine that much of what looks like the official world of art, with all of its authority and power is in some ways a delusion – a colorful, elaborate and impressive array but something of a pompous fantasy nevertheless. In its character, the institutional art world is somewhat like a religious empire, and like the church, would seem to be in contradiction to the personal creative impulse that produces its original value and authentic currency.

The scholars, critics, administrators, judges and dealers who mainly organize and steer the world of art seem to be overwhelmingly intellectual or well versed in art politics, economics and fashion but truly natural artists are not inclined to be like that because they are mostly too absorbed in the messy organic truths and mysteries of the creative act. This disparity between artist and art institution is somewhat useful but can lead to ignorance, suppression and dullness because the institutionalizing of art and the canonizing of approved artists can culturally diminish, obscure or deaden the valuable idea of art’s raw vitality and its elusive, divine nature.

‘Paint as you like and die happy’ said the writer and painter Henry Miller. It is good hearty advice. Unconsciously I have been painting the holy fool with its places and its companions for many years – not so much with the idea of art in mind but simply for the pleasure of painting pictures that amuse or delight me, pictures that remind me of my childhood or my inner state, paintings that flagrantly misbehave or under-achieve in order to be free. Now I see that my painting has been about some life-long enjoyment and adoration of an innocent sensibility.

The most joyous painting is not done for the art world, it is done for the inner world; it is a self delighting other-worldly thing – a getting lost in regression and solitude; a sub-literate, semi-delirious way to be with the spirited little fool in the depths of one's being for a while – there to invent one's art freely, and there to find enchantment, infinite surprise and the bright wondrous question ‘What is this?’

Of course no adult can become an innocent child again but they may be able to find an unbroken path through imagination, intuition and sensual memory - back to impressions of infancy or early states of mind, and through a fruitful experience of this connection develop an adult capacity to reliably access a condition of humility, equanimity, openness and wonderment that we might call mature innocence. Thus the holy fool may appear and the constricting curses of compliance, cleverness, sophistication and insecurity may begin to dissolve.

Memory of childhood can help in the recovery of creative self but one of the most radical ways back to a state of discovery and playful creation is the messy path of unexpected regression. There are painters who often experience this and have learned that painting teaches much about failure and redemption – the dynamic that lies at the heart of creativity. The artist needs to know how to lose the plot – how to not care and how to not know – and how to actually enjoy that freedom and understand what a blessed revitalizing state all of that mess can be.

It could go something like this: the painter might begin a piece of work with high hopes and set forth with an interesting or brilliant idea in mind, but all too soon the painting begins to fail, the idea collapses and ambition starts to sour. The transcription from the intellect to the canvas is looking lifeless and artless, and the painter is starting to feel despondent. It's not working! How often it is that the mind and the hand have lost touch with each other. The painter redoubles all efforts but this only makes things worse and regression is happening as dismay and disillusionment set in. Soon enough the painting is in a miserable mess and everything is in disarray. It looks awful and the painter is emotionally heavy with self-doubt and disappointment. The worst has happened, the situation is lost and the painter's ego is peeling away. Little is it understood but at last the painter is breaking free, albeit a free fall – into a disturbing state of not knowing. The regression deepens, reason has fled while tantalizing and delinquent infantile impulses are felt: the petulant desire to destroy the painting and get rid of the evidence; the painful reminder of inability and failure.

At this point one of the noble truths of creativity may begin to emerge: 'disillusionment precedes inspiration and growth'. So instead of abandoning the failure as many would, the artist recognizes an opportunity to be free and play about casually or recklessly in the ruins; to experiment and throw all cautious technique, all self criticism and high standards to the wind because now there is nothing to lose and nobody is watching. Before long the painter has forgotten the failure and becomes absorbed in the anarchy of spontaneous gestures and spirited whimsical play. The holy fool and originality are at hand. The artist is painting unselfconsciously and with happy abandon – and somewhat like a child. To hell with solemnity and proper art; the joy of discovery is all that matters now; the unprecedented textures, the way the colours have by chance smeared into each other: beautiful startling subtleties and unimagined miracles small and large to delight or shock the eye. And so it proceeds until the painter is staring in fascination at this revelation that the hands and impulses have created in a state of regression; a state that could not have been planned or organized - but simply happened when ego and ambition had sufficiently crumbled.

It is a way of painting. It is a way of living. It is a way of transcending the banal inhibited self and finding the divine. It is a struggling downward journey - this stumbling, daring and devout pilgrimage back to mature innocence and raw beauty; to the sublime joy and the natural intelligence and wisdom of the holy fool.

****

‘True art does not look like art’ said Lao Tzu, and if we can entertain this promising idea we might also begin to imagine that much of what looks like the official world of art, with all of its authority and power is in some ways a delusion – a colorful, elaborate and impressive array but something of a pompous fantasy nevertheless. In its character, the institutional art world is somewhat like a religious empire, and like the church, would seem to be in contradiction to the personal creative impulse that produces its original value and authentic currency.

The scholars, critics, administrators, judges and dealers who mainly organize and steer the world of art seem to be overwhelmingly intellectual or well versed in art politics, economics and fashion but truly natural artists are not inclined to be like that because they are mostly too absorbed in the messy organic truths and mysteries of the creative act. This disparity between artist and art institution is somewhat useful but can lead to ignorance, suppression and dullness because the institutionalizing of art and the canonizing of approved artists can culturally diminish, obscure or deaden the valuable idea of art’s raw vitality and its elusive, divine nature.

‘Paint as you like and die happy’ said the writer and painter Henry Miller. It is good hearty advice. Unconsciously I have been painting the holy fool with its places and its companions for many years – not so much with the idea of art in mind but simply for the pleasure of painting pictures that amuse or delight me, pictures that remind me of my childhood or my inner state, paintings that flagrantly misbehave or under-achieve in order to be free. Now I see that my painting has been about some life-long enjoyment and adoration of an innocent sensibility.

The most joyous painting is not done for the art world, it is done for the inner world; it is a self delighting other-worldly thing – a getting lost in regression and solitude; a sub-literate, semi-delirious way to be with the spirited little fool in the depths of one's being for a while – there to invent one's art freely, and there to find enchantment, infinite surprise and the bright wondrous question ‘What is this?’